Update 566 – Building a BBB Budget:

Can It Be Balanced by Billionaires?

Last weekend, Senator Kyrsten Sinema nixed BBB proposals to raise corporate, individual and capital gains tax rates to pay for the bulk of the bill. Scrambling to fill the close to $1 fiscal hole, Democrats have seized upon the billionaire tax option. The plan proposed by Senate Finance Chair Ron Wyden provides that billionaires will pay an additional five percent on income over $10 million, and an additional three percent on top of that on aggregate gross income over $25 million.

Today’s concerning report of GDP growth falling from 6.6 percent in the second quarter to 2 percent in the third underscores the urgent need for fiscal support of the stalling recovery. This update will focus on the so-called Billionaires’ Tax and the current economic conditions that have made it among the most tantalizing payfors, the biggest stumbling blocks facing BBB, which provides precisely that support.

Good weekends, all…

Best,

Dana

———————

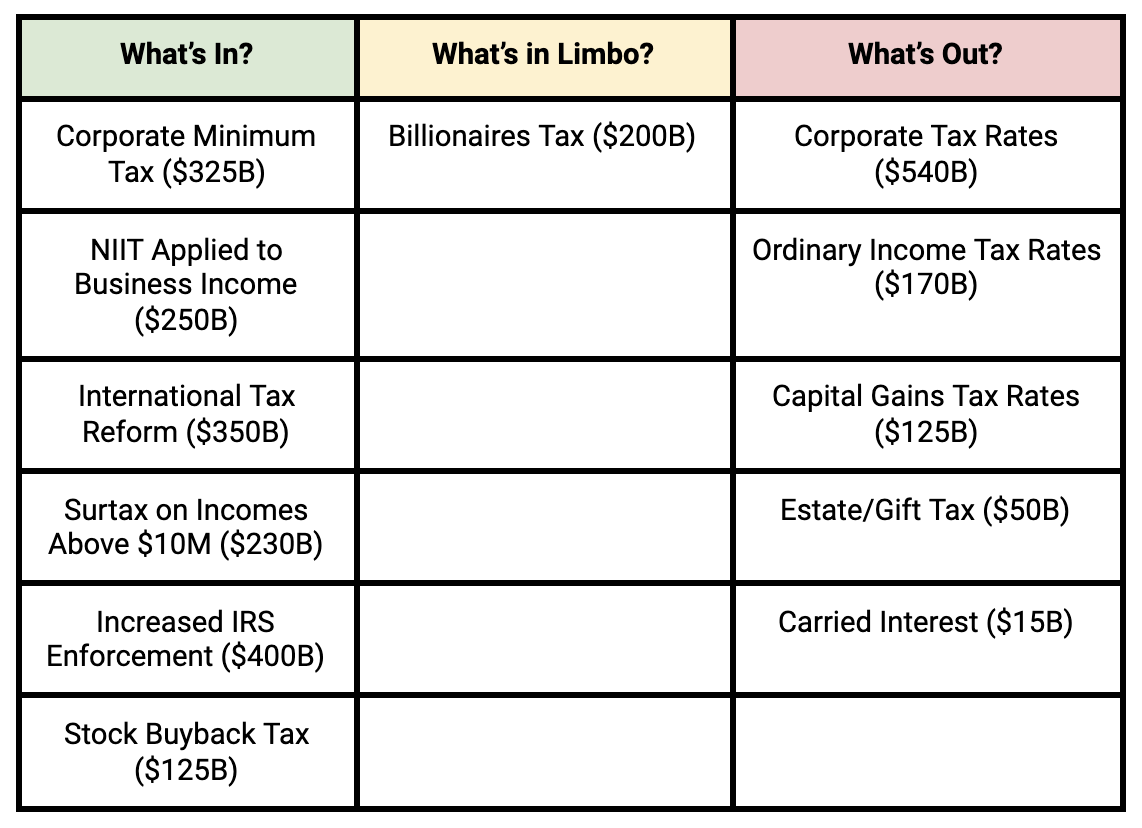

Last month, the House Ways and Means Committee passed a comprehensive revenue package for the Build Back Better Act. While the vast majority of Democrats are satisfied with the Ways and Means mark-up outcome, Sen. Sinema (D-AZ)’s sudden line in the sand jettisoned three major components of the revenue package, 26.5 percent corporate tax rate, 28.8 percent top capital gains rate, and 39.6 percent high-income rate. Stripping these three provisions out would blow a $830 billion hole in BBB. Sinema’s obstinacy has forced Democrats to search for creative methods to raise new revenue. Today new bill text was released, giving a clearer picture of where revenue raisers stand.

Current State of Major Revenue Raisers in Build Back Better Text

Concentration on Wealth Concentration

For decades, the United States has seen a widening income and wealth gap, leading to increased inequality and consolidation of wealth among the richest Americans. In 2018, the top three richest men were worth more than the bottom half of Americans. The number of billionaires in the US has risen from around 60 to more than 700 in the last three decades, with the total wealth of this group jumping from $240 billion to over $5 trillion. The taxes they’ve paid compared to their wealth has decreased by 79 percent. This immense growth in wealth combined with a lack of taxation creates an opening for revenue.

Billionaires pay essentially an 8 percent income tax rate, lower than the poorest Americans. Little of billionaires’ wealth and investment income is taxed. They often simply hold their assets, and even when it is passed onto their heirs, much of it goes untaxed due to the step-up in basis loophole. In the rare instances, they do sell their assets, they only pay a 23.8 percent capital gains tax, far lower than the income rate.

The pandemic has exacerbated these wealth disparities. American billionaires have grown 70 percent richer over the course of the pandemic, with their worth growing from $3 trillion in March 2020 to over $5 trillion in October 2021. While billionaires grew wealthier, working-class Americans struggled to make ends meet and felt the devastating economic impacts of the pandemic.

The Wyden Proposal

On Tuesday, Senate Finance Committee Chair Ron Wyden introduced his Billionaires Income Tax proposal, which would effectively create a mark-to-market tax system for the richest ∼1,000 individuals. Under current law, the capital gains tax is only triggered at the point of sale, meaning the very rich can often defer their paying taxes indefinitely by borrowing against their assets rather than selling off their gains. This allows the wealthiest families to pay a lower effective tax rate than teachers, nurses, and janitors who earn their income from labor.

Were Wyden’s bill to become law, this mark-to-market feature would apply to households with a net worth of $1 billion or an annual income of $100 million for the three prior consecutive years. The bill would immediately levy an initial tax on billionaires’ publicly traded assets which could be paid over five years. For each subsequent year, billionaires would have to pay annual taxes on their unrealized gains, with unrealized losses allowed to be carried forward to offset future gains or backward up to three years to offset past gains and claim refunds.

The proposal would tax non-publicly traded assets — real estate, private business, artwork — at the point of sale or inheritance, avoiding the need to assess their annual value. Since this would create a tax preference for non-publicly traded assets, the bill includes an interest deferral charge to equalize the burden on those assets. This interest charge would be calculated at the short-term federal rate plus one percent for each intervening year the asset was held. That tax would be capped at 49 percent of the total value.

Wyden’s Billionaire Income Tax has a handful of special rules in place to ensure compliance and prevent avoidance:

- The tax threshold for trusts would be $100 million in assets or $10 million in income to make it harder for billionaires to split their assets

- Gifts and bequests to non-spouses would trigger the capital gains tax, though donations to charity are exempt

- Limitations on billionaires’ use of tax loopholes such as deferred compensation, annuities, life insurance, small business stock, and opportunity zones

The revenue Wyden’s proposal would generate is not easily estimated, but likely upward of $200 billion over the next ten years. There are also concerns over the constitutionality of this mark-to-market scheme. The issue hinges on the interpretation of the 16th Amendment’s use of the word “income” and whether or not unrealized gains qualify as such. Even with a right-wing Supreme Court, the judiciary generally gives broad latitude to Congress’s ability to levy taxes, and if the billionaires’ tax would be found unconstitutional, it could eviscerate entire sections of the existing tax code.

Prospect of Passage and Implications

Levying a tax on billionaires helps restore some measure of fiscal equity, even if it is on a very narrow base. The tax class here is 700 to 1000 taxpayers at the most. And it leaves most other high-income earners out of the discussion. To fully fund a sound social safety net, like the one progressives continue to propose, both the upper and upper-middle classes ought to be considered for tax hikes, including corporate, individual income, and capital gains taxes. While upper-middle-class taxes were nixed by President Biden’s $400,000 income no-tax-hike pledge, much of the upper class is avoiding a tax increase when the billionaire tax is swapped in for corporate, individual income, and capital gains tax rate increases.

The political upside to a billionaire’s tax is clear. Taxing the ultra-wealthy polls incredibly well: 68 percent of voters support Senator Warren’s wealth tax proposal, which targets a similar group of individuals as a billionaire’s tax. Increasing taxes on these households is politically popular, but it needs to be weighed against the potential revenue losses of not pursuing broader tax reform.

A billionaire’s tax entering the realm of legislative discussion is, though, a seismic shift in how politicians discuss tax policy. Proposals for similar concepts have mostly been relegated to campaign pitches, white papers, and the occasional legislative text. Until now, these concepts had never entered the final stages of negotiations.

For this reason, we should be skeptical of the odds this billionaire’s tax becomes law. Senator Sinema may have tentatively agreed to the concept in hopes moderates in either chamber would come out against it and sink larger portions of the Build Back Better Act. And she seems to be right. Despite progressives seizing on the opportunity to soak the richest of the rich, Senator Manchin has come out against the proposal in favor of a 15 percent “patriotic tax.” And since Manchin’s seal of approval is critical to the final agreement, the billionaire’s tax may have low odds of passage for the present.