Update 573 — A Number of Anomalies:

Takeaways from Nov. BLS Jobs Report

You could get the wrong idea about the jobs picture in the U.S. from this morning’s top-line figure in the BLS jobs report for November. Despite an anomalous showing of just 210,000 jobs added and the service sector shedding jobs, unemployment dropped to 4.2 percent and wages are running even with inflation.

Trying to describe and predict job market trends presents a challenge. As the recovery gains strength and supply constraints ease slowly, inflationary trends will abate — but soon and by enough to forestall Fed rate hikes that could wreck the party? As more jobs are added, that brings back the pandemic-suppressed labor force? In this update, we examine the labor market on the macro level, assess how the new-found worker power came to be and the factors behind the trends.

Good weekends all…

Best,

Dana

————

As the economic recovery continues apace, 210,000 jobs were added last month. Recent months were also revised upward by 82,000 jobs, bringing the monthly average to 555,000 new jobs per month for the year to date. The labor market should continue to tighten, but the economic outlook is still foggy given countervailing pressures unique to the pandemic recovery, such as the emergence of the Omicron variant. Workers are capitalizing on these conditions and their newfound bargaining power to secure better working conditions and pay.

For low-wage and service sector jobs, the ‘Great Resignation’ has pushed wages up as these laborers head toward better-paying jobs and work environments. At the same time, a labor shortage among truckers and longshoremen is affecting the supply chain, causing many ports to become clogged up with shipping containers. The White House has argued the solution lies in the examples of the industries recovery from the Great Resignation: better pay and conditions for these workers to incentivize more people to join the industry.

A Tightening Labor Market

The economy is poised to recover far faster than after the 2008 financial crisis. Unemployment has fallen to a post-pandemic-start record of 4.2 percent. This is partially a base effect as millions of people, disproportionately women, have dropped out of the labor force for various reasons including the pandemic and a lack of re-entry from retirement. The labor force participation rate stands at 61.8 percent, recovering nearly halfway from its pre-pandemic peak of 63.4 percent in January 2020. But the Prime-Age Employment-Population Ratio has recovered more strongly with that rate now sitting at 78.8 percent, only 1.7 percentage points below its pre-pandemic peak of 80.5 percent. Moody’s Analytics argues that a Prime-Age Employment-Population Ratio of 80 percent is in line with full employment and estimates we will hit that by the fourth quarter of 2022.

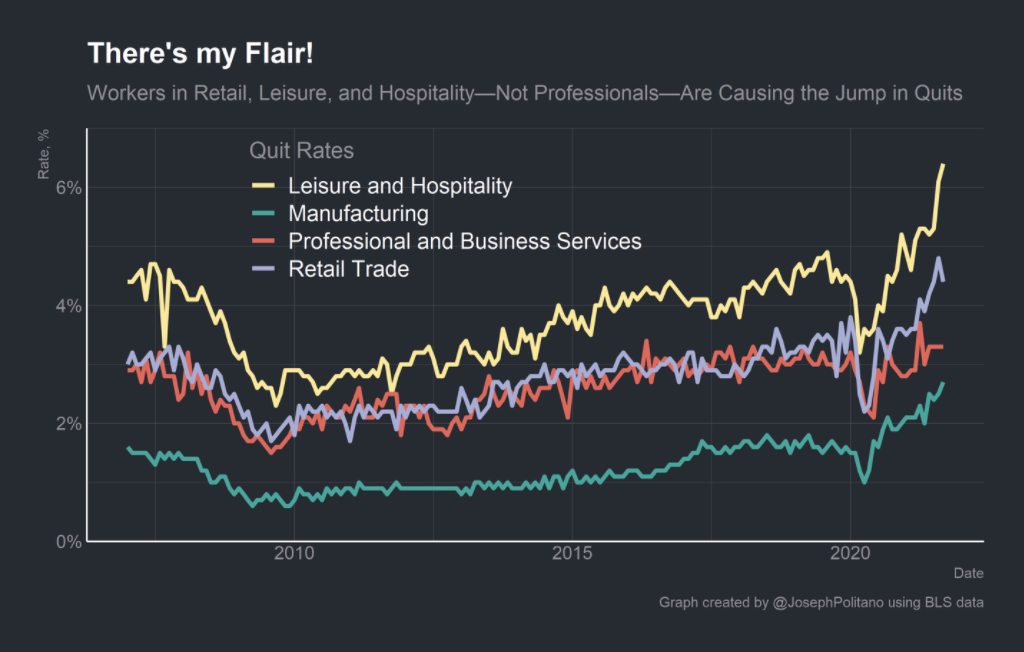

Meanwhile, workers are quitting at record rates in pursuit of better pay or conditions, as well as trying to avoid the pandemic. Over 4.4 million workers handed in their notice in September, representing a record 3 percent of the workforce, which was overwhelmingly concentrated in low-wage and service sector industries. The rapid increase in the quits rate has exacerbated the labor shortage, and when combined with the suppressed labor force participation rate, workers have the ability to increase their demands and find better-suited jobs.

Until the pandemic is resolved, millions of people won’t return to the labor force, which means labor shortages will persist. This lack of supply will continue to increase the bargaining power of labor. That is why workers have engaged in some of the boldest labor demonstrations in recent history.

Workers’ New Strength

The most direct impact of the tightening labor market is robust wage growth. Average earnings for hourly employees are 8.9 percent higher than pre-pandemic wages. While wages have been rising across the board during the past year, it is even more pronounced for workers in traditionally lower-income sectors. Employers have to adapt their business models that have been structured to thrive in a weak labor market. In the short term, this transition to a “worker’s economy” is leading to supply chain problems. Seasoned employees are being replaced with raw recruits or not replaced at all — not so much a labor brain drain as a labor reshuffle. But once employers come to grips with the new realities of the labor market, employee enlistment and retention will rebound.

The United States is experiencing some resurgence in organized labor action and unionization. Though organized labor has been in decline for several decades, particularly in the private sector, this year has seen a sharp rise in the strikes in response to the failure of many large companies to address pandemic-related health and financial concerns from workers. In October alone, almost 100,000 workers were authorized by unions to go on strike, including employees at 14 separate John Deere manufacturing plants, Kaiser Permanente, and Kellogg’s.

Public support for labor unions is also on the upswing, with 68 percent of Americans approving them, the highest levels since 1965. With the backing of the public, labor unions have attempted this year to make major inroads into sectors that have been traditionally hostile to workers organizing, most prominently at Starbucks and Amazon. The union drive at Amazon’s Bessemer fulfillment center was dealt a major win this week when the National Labor Relations Board ruled that management engaged in deceitful and improper actions to subvert a union vote held in March and would have to hold a second election. Unfortunately, due to outdated labor laws, Amazon was not given any civil monetary penalties for their actions, and there is a long track record of companies repeating illicit union-busting behaviors.

Further Improvements in Terms and Conditions?

While some of the labor conditions are temporary and out of the hands of policymakers, many more can be addressed by Congress or the Federal Reserve. Below are two policy variables that stand to accelerate improvements in the labor market:

- Build Back Better Act: This bill would make critical investments in childcare, homecare, and pre-K — all of which have proven to improve labor force participation and total employment, particularly among low-income mothers. Moody’s estimates that if BBB is passed, total employment will grow by 1.3 million by 2024, helping ease the pressure in the labor market. Additionally BBB’s investments in workforce development and higher education will increase labor productivity in the long term.

- Monetary Policy: The Federal Reserve can also play a role in ensuring a robust, labor-driven recovery. By maintaining an accommodative monetary policy, the Fed can incentivize job and wage growth. One suggestion for structural reform is for the Fed to tie the economic recovery to the Black unemployment rate or the Prime-Age Employment-Population Ratio. By focusing on groups that have historically lagged behind the overall recovery and better measurements of labor utilization, the Fed can ensure a more equitable recovery.

The Path Ahead

As the labor market continues to recover, economic forecasts are murky. It can not be understated how unique it is to have tight labor market conditions even while total employment remains 3.9 million below the pre-pandemic peak. While upward wage growth is a positive sign, there is no guarantee that those gains will be maintained. The gains may be wiped out by rising prices if supply chain issues persist. Congress can help bring economic certainty, and give workers more power in the long term, by immediately passing the Build Back Better Act to ensure that the labor market can keep up with rising demand in the coming months and years.