Update 676 — Run Halted, SVB Dust Settles

Implications for Regulation and US Economy

The sudden collapse and seizure of the Silicon Valley Bank Financial Group (SVB) and Signature Bank over the weekend triggered memories of the fear, anxiety, and economic turmoil that followed the bank failures of the 2008 financial crisis. The Biden administration, the Fed, and the FDIC’s announcement that banks had been taken into receivership and depositors made while stanched further bank runs but left questions about whether “too big to fail” is now institutionalized policy, given all, even uninsured, if its depositors protected, even if SVB and have failed.

Today, we look at the curious circumstances surrounding the collapse of SVB and Signature, consider regulators’ rapid response to protect depositors and secure the banking system, and discuss potential reform and investigations headed our way.

Best,

Dana

______________

Nation’s 16th Biggest Bank Fails — Is that Systemic?

The SVB collapse marked the second-largest bank failure in U.S. history and the largest since the 2008 financial crisis. The 40-year-old firm was known for providing banking services to tech startups and venture capital firms and its growth paralleled that of the tech sector. In 2015, it claimed to serve 65 percent of all U.S. startups. By the end of 2022, over half of the bank’s loan portfolio constituted lending to venture capital and private equity firms.

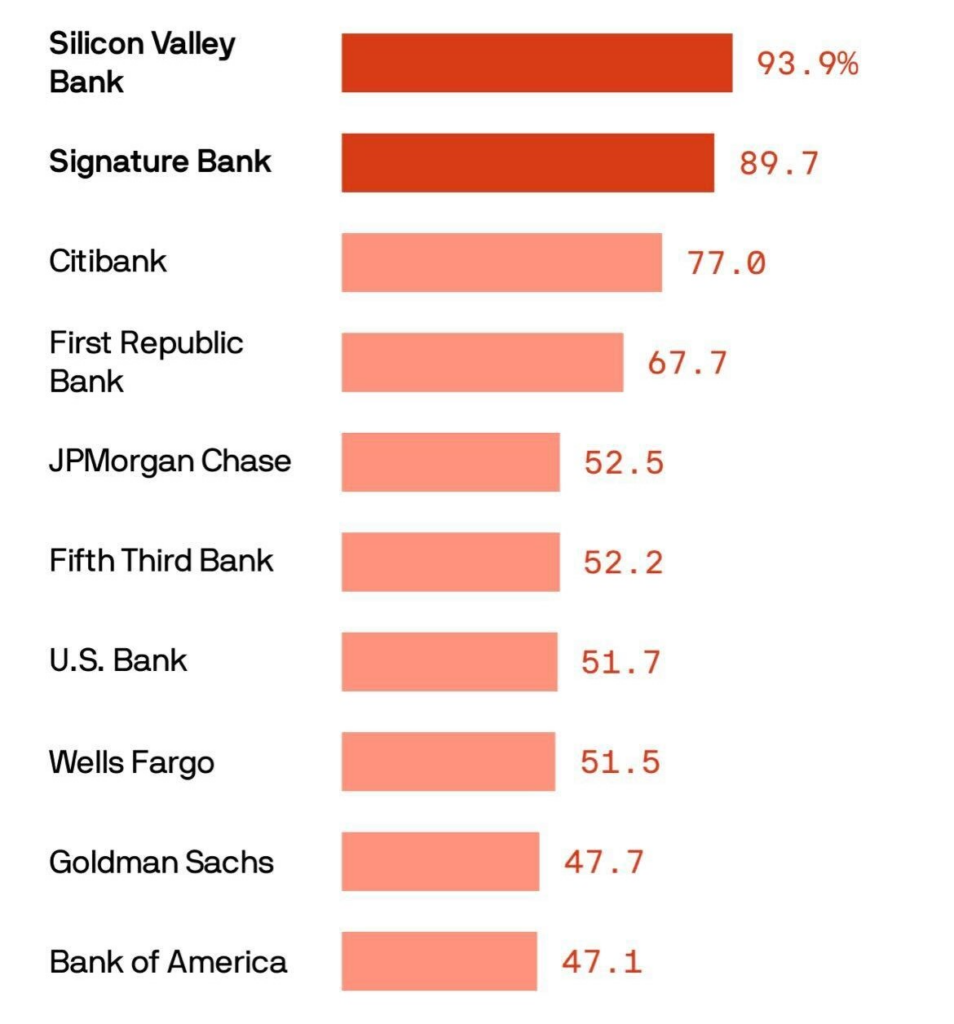

More than 90 percent of its customers held deposits at the bank exceeding the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s $250,000 deposit insurance limit. By the end of 2022, about $151 billion of SVB’s $212 billion in customer assets were uninsured deposits.

Percent of Uninsured Domestic Deposits

as of 12/31/22

Source: Axios Visuals Data: S&P Global Market Intelligence

As client tech startups grew over the past three years and parked cash as at SVB, the bank invested heavily in long-term Treasury bonds whose values fell as the Fed embarked on its steepest series of interest rate hikes since the early 1980s. When SVB’s customers began pulling their deposits, the bank announced last Wednesday its sale of approximately $21 billion in unmatured treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities, resulting in an after-tax loss of approximately $1.8 billion in the first quarter of 2023.

SVB planned to recoup losses from the securities sale by raising fresh capital and announced a $2 billion stock offering. But the next day, investors and depositors tried to pull $42 billion, and triggered a run on the bank. At the close of business on Thursday, SVB had a negative cash balance of $958 million and on Friday, California’s bank regulator, the Department of Financial Protection and Innovation, filed an order to take possession of SVB, leading to an FDIC seizure of control of Silicon Valley Bank and its assets.

SVB and Signature Deemed Systemic

Regulators including the Fed, FDIC, and Treasury worked through the weekend, in consultation with legislators, to protect depositors and the broader banking sector. In the race to address the fallout before Monday, regulators held a failed auction in which none of the largest U.S. banks bid to acquire the commercial bank.

On Sunday, New York-based Signature Bank, which provided lending services to law firms and real estate companies, was closed by New York’s state chartering authority. With $110 billion in assets, the bank’s customers held roughly $88 billion in deposits, about 90 percent of which were uninsured.

With the failure of two large banks, regulators decided to take decisive action to reassure customers that their deposits were safe and taxpayers that they were not being asked to bail out banks. In emergency meetings over the weekend, federal regulators decided to reassure depositors that all their money would be accessible, even beyond the insured amount, invoking the systemic risk exception.

In a joint statement, the FDIC, Fed, and Treasury Department announced plans to

- Make Depositors Whole – Regulators allowed all depositors of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank – both insured and uninsured with deposits surpassing the FDIC’s $250,000 deposit insurance limit – to access all their money through the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF), with any losses to the fund recovered by a special assessment on banks. The decision to grant this exception to uninsured depositors was driven in part by exclusive bank deals that SVB had some clients sign, limiting their ability to diversify. Fed Chair Jerome Powell supported a similar move during the Bank of New England bailout in 1991, a remedy conceptually at odds with the spirit of Dodd-Frank. In this case, deposits will be recovered by dipping into the DIF which is funded by the banking sector itself. The decision to dip into the DIF rather than use taxpayer funds may help offset moral hazard concerns, as the DIF will be depleted following customers’ recovery of their funds held by SVB.

- Create a new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) – To provide liquidity against high-quality securities and eliminate institutions’ need to quickly sell those securities in times of stress, the Fed announced that it would create a new BTFP which would provide loans for up to one year to banks, savings associations, credit unions, and other eligible depository institutions pledging U.S. Treasuries, agency debt and mortgage-backed securities, and other qualifying assets as collateral. As a backstop for the BTFP, the Treasury Department will make up to $25 billion available from the Exchange Stabilization Fund.

By Monday, Silicon Valley Bank was operating as the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara, a “bridge-bank.” In light of the measures effectively declaring the failures of SVB and Signature threats to the financial system, regulators said that they had greater flexibility to sell the bank.

Reform on the Horizon?

Beyond implementing measures to respond to immediate bank failures and prevent a wider threat to the financial system, regulators and legislators must now confront the causes of the failures of these banks and take action to shore up systemic weaknesses that could have prevented their falls. A fundamental failure by the banks to effectively manage the risk of interest rate hikes was clearly responsible, but could stricter regulation have avoided the current situation?

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the passage of Dodd-Frank provided critical protections to the banking sector, including capital requirements for banks to protect against the danger of bank runs and stress tests to ensure banks were strong enough to respond to periods of existential stress. In 2018, S.2155, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act was signed into law. Title IV of the bill rolled back or “tailored” some of these regulations. It adjusted:

- Capital Requirements – increased the asset threshold at which certain enhanced prudential standards would apply from $50 billion to $250 billion while allowing the FRB discretion in determining whether a financial institution with assets equal to or greater than $100 billion must be subject to such standards.

- Stress-Test Requirements – increased the asset threshold at which company-run stress tests were required from $10 billion to $250 billion.

A review of capital standards is already underway. Last year, Federal Reserve Vice Chair of Supervision Michael Barr announced plans to conduct a “holistic review” of capital standards, saying that such a review should be a periodic feature of bank oversight.

Ten Senate Banking Republicans, led by Ranking Member Tim Scott, sent a letter to Chair Powell expressing concern that yet-to-be-proposed capital requirements might not sufficiently tailor capital requirements for banks with assets below the $250 billion asset threshold. The VCS capital requirement review and S.2155 were the subjects of debate in the House Financial Services Committee and the Senate Banking Committee only last week when Fed Chair Jerome Powell delivered his semi-annual testimony before Congress, with Senator Bill Hagerty (R-TN) asking Powell whether he would support proposed adjustments that were “aggressive” or contradictory to the spirit of S. 2155.

Yesterday, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), who vehemently opposed the 2018 legislation, and Representative Katie Porter (D-CA), led a group of Democratic legislators in introducing the Secure Viable Banking Act which would repeal Title IV, reinstating the standards previously enshrined in Dodd-Frank. Earlier this week, Representative Maxine Waters (D-CA) said that she was working to schedule a hearing on the collapse of SVB “as soon as possible.” The Justice Department and SEC have reportedly begun separate investigations into the collapse of SVB. Additionally, the Federal Reserve announced that Barr was leading a review of the oversight of Silicon Valley Bank which will be released on May 1.

The collapse of SVB and Signature and the response of market participants and regulators have cast fresh light on a welter of financial regulatory issues and policy reform ideas. Some of these directly bear on and complicate the consideration of upcoming monetary and other regulatory policy issues. More on these issues on Friday.