Update 563 — Labor Market Review:

Participation Down Tho Benefits Cut

The U.S. added 194,000 jobs in September but 183,000 people dropped out of the labor force, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ September jobs report, released Friday. It’s the first report since federal unemployment programs ended on Labor Day, offering yet more evidence that pandemic-era unemployment benefits didn’t hold the labor market back much. Other factors, like the Covid delta wave, played a bigger role.

The current state of the labor market has important implications for ongoing policy debates, particularly regarding the macroeconomic effect of enhanced unemployment benefits and the two major infrastructure and social policy bills moving through Congress. Below, we evaluate these implications and what they suggest for the path forward.

Until next week…

Best,

Dana

——————————

State of the Labor Market

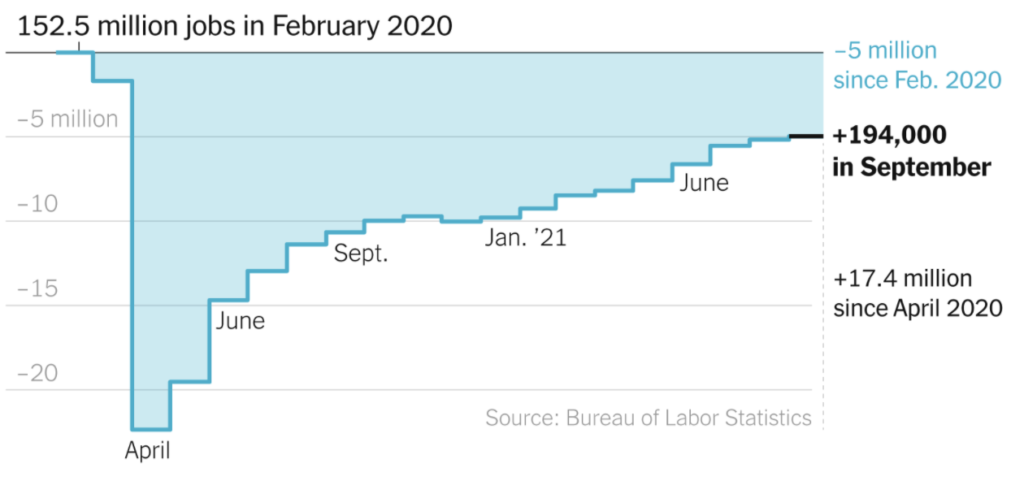

After a summer of robust job growth, September saw a lower-than-expected job increase of 194,000, dragging the three-month average down to 550,000 jobs added per month. The effects of the delta variant aside, job growth may have been suppressed by BLS adjustments for seasonality. Public education alone saw 123,000 jobs lost while the private sector as a whole grew by 317,000 jobs. The pandemic may have resulted in a drop in public education jobs for September, but the seasonal adjustments could have altered the numbers more than necessary, reducing the total jobs number for the month.

Cumulative Change in Jobs Since Pandemic Start

Graph Produced by the New York Times

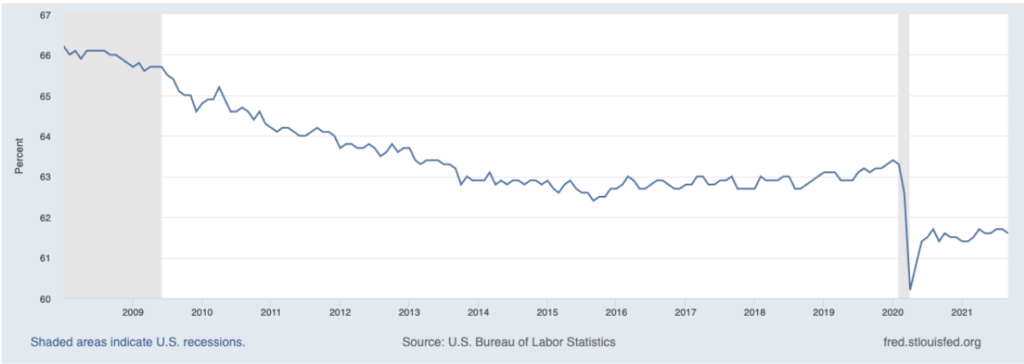

The unemployment rate fell from 5.2 percent to 4.8 percent, a pandemic recovery low. But part of the reduction could be attributed to 183,000 people, mainly lower-income workers, dropping out of the labor force. Labor force participation has risen from its pandemic low of 60.2 percent to 61.6 percent but is still about 1.5 basis points below the pre-pandemic norm of roughly 63 percent. More than 300,000 women over 20 dropped out of the labor force in September while 182,000 men joined. This is part of a larger structural imbalance in labor force participation: the female labor force participation rate is 55.9 percent, compared to 67.7 percent among men.

Labor Force Participation Rate, 2008-Present

Graph Produced Using Federal Reserve Economic Data

Meanwhile, the “Great Resignation” continues, as many workers are quitting, demanding better quality jobs, and refusing to return to low-wage, service sector jobs out of pandemic concerns, childcare responsibilities, and frustration with poor working conditions. Workers have been quitting at a record pace, with August having the highest number of quits on record at 4.3 million, around 3 percent of the overall labor force. With job openings at 10.4 million, workers are seeking to leverage the openings to find better compensation and job quality, resulting in businesses raising wages to attract workers over the course of the year. Just in September, the bidding up led to a 0.6 percent increase in average nominal wages month-over-month, primarily concentrated in low-wage jobs. Average hourly wages rose to $30.85 last month, up from $29.50 last year.

While the labor market is slowly recovering, the U.S. is still roughly 5 million jobs below the pre-pandemic peak, highlighting the involuntary unemployment still plaguing the economy. Further fiscal support to bolster the labor market over the long term is still very much merited, particularly for those workers who bore the brunt of the pandemic.

The Labor Market and Unemployment Insurance

The September jobs report provides strong evidence against claims that the American Rescue Plan’s modest Unemployment Insurance benefit enhancements were keeping people from going back to work. For months, Republican governors and state legislators cut expanded UI benefits short — eliminating an important boost to consumer spending with no discernible improvement to labor force participation or job growth in their states.

Now, with 8 million fewer UI recipients than at the start of September when expanded benefits expired nationally, the predicted wave of hiring that conservatives were promising has still failed to materialize. Recent economic studies have found that the states which cut off enhanced federal UI benefits saw little to no positive effect on employment.

In fact, cutting short UI benefits for millions of laid-off workers may have long-term adverse effects on the macroeconomy. UI benefits are simultaneously effective at economic stimulus and poverty reduction:

- The fiscal multiplier effect of expanded UI benefits is estimated at 1.5, meaning that every $100 the government spends in UI produces $150 in total economic activity.

- In 2020, 4.7 million people were kept from falling into poverty directly because of the benefits they received through expanded UI benefits.

- The Economic Policy Institute estimates that UI benefit cuts will reduce annual incomes by $144 billion and consumer spending by $79 billion over the next year, seen as likely to create a negative feedback loop where reduced incomes and consumer spending lead to further job loss, leading to even less consumer spending.

UI is a critical economic backstop, and Democrats have a chance to build on their work in the American Rescue Plan. A proposed bill sponsored by Sen. Wyden and Rep. Beyer, the Unemployment Insurance Improvement Act, would permanently reform the UI system reducing state-by-state disparities and requiring a minimum of 26 weeks of compensation.

Labor Market’s Path Ahead, Policy Implications

Recent economic data — as well as the effects of the delta variant, ongoing supply chain bottlenecks, and changes in the labor market — suggest that the economic recovery from the pandemic is still incomplete, particularly for women and people of color. In economic projections released last month, the Federal Reserve revised down its expectation for GDP increase in 2021 to 5.9 percent in 2021 and 3.8 percent in 2022, compared to its June projections of 7.0 percent and 3.3 percent, respectively.

At the same time, Fed policymakers, citing substantial further progress in the labor market, have increasingly signaled that they will begin to taper the $120-billion-a-month asset purchases started early on in the pandemic. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has consistently maintained an accommodative monetary policy over the past year and a half to support the labor market. But the persistence of elevated inflation readings may put more urgency on the Fed to wind down its asset purchases and potentially move up the timetable for interest rate hikes.

As the Fed is expected to soon scale back its monetary support, Congress has an opportunity to make long-term improvements to the labor market by passing both the Bipartisan Infrastructure bill (BIF) and the Build Back Better Act (BBB). The continuation of lower labor force participation (with larger drops experienced by women) while job openings remain high suggests that accommodative monetary policy’s ability to support the labor market has structural and circumstantial limits.

The BIF would create good jobs for physical infrastructure projects. Structural reforms included in the BBB, such as paid leave, universal pre-K, home and community-based care, and childcare, are needed as well to boost labor force participation — particularly among caregivers, disproportionately women — and to create better quality jobs. Funding for workforce development in BBB would help fill the demand for workers in industries with elevated quit rates and vacancies.

The benefits promised by these bills to the labor market are significant: Moody’s Analytics estimates that passing BBB and BIF will raise real GDP growth to an average of 4.2 percent per year under the Biden administration and an average of three percent real GDP growth per year over the next decade. Job creation would increase by 12.9 million during Biden’s term and 19.1 million over the decade. Crucially, key provisions in the bill such as childcare and pre-K would increase both labor force participation and labor productivity. These bills are designed to help generate a broad, deep, and durable recovery, the measure of which will be unemployment under four percent and labor participation rates back to the mid-60s.