Update 638 — Congress OKs FY23 CR

Final Budget Can Kicked to December

Yesterday, the Senate passed a continuing resolution to fund the government through mid-December, by a vote of 72-25. And just earlier this afternoon, the House passed the measure, but with much less bipartisan support, 230-201. With this must-pass item completed, Congress stands adjourned until after the midterm elections in November. The CR includes $12 bn. in assistance for Ukraine, $20 bn. for water projects in Jackson, MS, $1 bn. for low income heating assistance, $2.5 bn. for New Mexico disaster recovery, $2 bn. for the CDBG program, and more.

But Congress will, once again, start the new fiscal year tomorrow without a single one of its twelve appropriations bills completed. This week’s continuing resolution reflects a budgeting process in Congress that relies increasingly on continuing resolutions, creating a precarious precedent for how the government is run. We cover the CR and the problem with CRs in today’s update.

Good weekends all,

Dana

————————————

Deadline Delayed until December

Congress worked rapidly this week to pass a continuing resolution before tonight’s midnight deadline. Yesterday, the Senate passed a bill that would fund the government at its current levels through December 16. The House passed the same bill this afternoon, averting a potential government shutdown. The president is expected to sign the bill later today.

The bill also includes various additional appropriations and language, such as:

- $12.35 billion in assistance for Ukraine

- $1 billion for the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)

- $2.5 billion for New Mexico communities recovering from the Hermit’s Peak/Calf Canyon Fire

- $2 billion for the Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery program

- $20 million for water and wastewater infrastructure improvements for Jackson, Mississippi

- Language allowing FEMA to obligate up to the full year amount available under the continuing resolution for the Disaster Relief Fund if needed to respond to declared disasters including Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico

- Re-authorization of FDA user fee agreements for five years

Sen. Joe Manchin agreed to strip his permitting reform proposal from the bill on Tuesday night in order to pave the way for the rest of the continuing resolution, as he did not have the 60 votes needed to pass it. Manchin’s proposal managed to anger conservatives and progressives alike. Progressives like Bernie Sanders, Tim Kaine, and others opposed its inclusion in part due to the provision greenlighting the controversial Mountain Valley Pipeline. Several House Democrats, including Appropriations Chair Rosa DeLauro, expressed concerns about attaching permitting reform to the resolution. Republicans were opposed in part due to what they saw as a betrayal by Manchin over the Inflation Reduction Act, and preferred a separate proposal by Senator Shelly Moore Capito.

The bill also does not include the $27 billion that the Biden administration had hoped to secure for COVID-19 and monkeypox aid. On Tuesday, Delauro remarked, “while the bill provides a bridge to the omnibus, it is not perfect. I am saddened the continuing resolution does not fully rise to meet some of our country’s most urgent needs, including the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and monkeypox outbreak.” Republicans have been reluctant to pass new funding for COVID relief efforts, citing unspent funds from previous rounds of aid and concerns about deficit-financed spending. A bipartisan deal on a fully-offset $10 billion COVID supplemental fell apart earlier this year, and legislators have not reached a new agreement to shore up needed funding for vaccines, testing, and therapeutics.

The Unfinished Business

The continuing resolution will fund the government through mid-December when Congress will need to pass either an omnibus or a new continuing resolution. Come December, the omnibus will offer Congress another chance to address issues that were not addressed in this week’s bill, like funding for COVID-19 and monkeypox.

While the CDC and the Health Resources and Services Administration’s HIV/AIDS Bureau have freed up money intended for HIV to be used in the monkeypox response, this is not an ideal solution. It is administratively cumbersome and unsustainable in the long-term. While reported monkeypox cases have been declining, the need for additional funding has not. Community clinics have not received the same kind of financial support for their vaccination and testing efforts that they did early in the COVID-19 pandemic. Offering support to community providers is an important part of the public health response, particularly considering the efficacy of the monkeypox vaccine. Advocates and the White House hope to secure funding for the monkeypox response in the omnibus.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has said that he will attempt to find another vehicle for permitting reform later in the year in order to both honor his deal with Manchin. He may seek to ensure that the green energy transition is able to take place with the necessary speed to achieve the goals of the Inflation Reduction Act’s climate provisions. While Manchin’s proposal would have included language undesirable to environmentalists, like greenlighting the Mountain Valley Pipeline, some advocates have talked about the need for reforms that would bring renewable energy onto the grid in a timely manner. There is discussion of attaching a permitting reform proposal to either the omnibus or the National Defense Authorization Act. Both would face continued opposition from Democrats in the House and Senate who have urged leadership to bring permitting reform to the floor as a stand-alone bill.

Whether or not Congress can agree on an omnibus by December may depend in part on the results of November’s midterm elections. If Republicans take control of one or both chambers, they may decide that it is in their interests to get the omnibus out of the way to leave room on the legislative calendar for their own priorities. Alternatively, they may decide to push the issue off until the start of the next Congress, where they would have more leverage over the final product.

Continuing Resolutions Continue

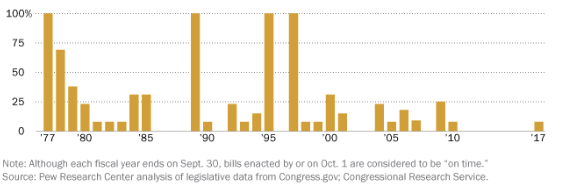

Congress was not able to pass an omnibus for Fiscal Year 2022 until March – over five months after the October 1 deadline – which contributed to the delay in getting this year’s budget process started. The President did not release his budget proposal until the end of March, nearly two months late. This year’s continuing resolution is another in a long line, highlighting Congress’s reliance on temporary funding measures in recent decades. The last time that Congress was able to pass all 12 of its regular appropriations bills on time was 1997. From 1997 to 2019, an average of at least five continuing resolutions were passed before the appropriations process for the year was completed, providing an average of five months of funding. And in all but three of the fiscal years since 1977, Congress passed at least one continuing resolution.

Percentage of Stand-Alone Appropriations Bills Passed on or Before Oct. 1 Each Fiscal Year

Source: Pew Research Center

Although increasingly a normal part of the budget process, continuing resolutions can pose problems for government agencies. When a continuing resolution is passed maintaining funding at the previous fiscal year’s levels for months at a time, agencies can experience budget cuts in real terms. They may also not receive money to implement programs Congress has already authorized but not yet appropriated funds for, delaying important projects.

Given Congress’s long-term inability to limit its use of continuing resolutions, Congress must reform the budget process. Budget process reforms are often discussed in Congress, but have never had significant enough support behind them to gain momentum. Moving to a biennial appropriations process rather than an annual one is an option that has been proposed numerous times over the years.

While this change would limit Congress’s ability to adapt the budget to changing circumstances each year, it would also allow for more breathing room between the passage of one budget and the deadline to pass the next. It could also free up time and resources for members involved in the appropriations process to devote to other priorities. But biennial appropriations alone will not resolve delays caused by partisan divisions — a growing factor in recent years, particularly in an evenly divided Senate and narrow House majority. Given that massive overhauls of the budget process are still a distant possibility, for now Congress seems poised to continue the cycle of lengthy continuing resolutions.